CREMONA, Italy - When the

Duke of Milan’s daughter Bianca Maria was about to get married, her father gave

her the town of Cremona as part of her dowry. He could do that you see, for

1441 was a time when Italian cities were the personal property of the rich and

powerful.

Bianca Maria didn’t do much

with Cremona, and for more than a hundred years the town didn’t do much with

itself either. That is until the 16th century when Andrea Amati came along and

developed the first modern violin. Through Armati, his sons and their students,

Antonio Stradivarius and Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesu, Cremona made history and

secured its place as the violin capital of the world.

It is hard to talk about

Cremona without talking about violin making, although there are other things to

talk about. The origins of the town go back more than 3,000 years making

Cremona one of the oldest towns in northern Italy. And while the Venetians, the

French, the Spanish and the Austrians all conquered Cremona at one time or

another, all of that history is completely over-shadowed by the music.

It hits you right away.

Walking from the train station, down the Via Palestro on my way to the center

of town, the honeyed strains of Vivaldi and Paganini, Tartini and Boccherini

floated out from the buildings. It was like being in a movie with the sound

track running.

The music was coming from

the privately operated violin workshops that are the commercial backbone of the

city. It was in a workshop just like the ones I was passing that Amati,

Stradivari and Guarneri del Gesu worked.

What those old Masters

accomplished was nothing short of a musical miracle, and for centuries scholars

and scientists have been trying figure out just how they managed to build such

magnificent instruments. Now researchers say the secret lies in the remarkable

even density of the wood the violin masters used.

It really wasn’t a secret.

Any of the violin artisans working in Cremona today could have told them that.

The real trick would have been to figure out how the old masters knew what wood

to choose, and where to find it.

|

| Maestro Stefano Conia |

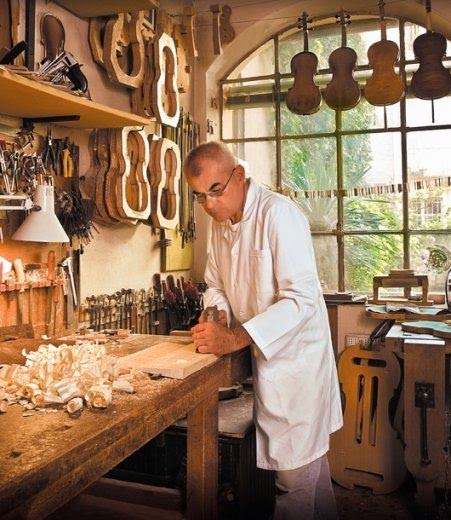

Talking to Maestro Stefano

Conia, founder of the Italian Association of Violin Makers, he tells me that

the method he uses to select the wood for his violins is exactly the same

method Stradivarius and the other Cremonese violin masters used hundreds of

years ago.

Like those old masters,

Maestro Conia uses a special wood found in the Paneveggio Forest, high on the

slopes of the craggy Dolomite Mountains in Italy’s northern region of Trentino.

The unique honeycomb structure of the forest's red spruce trees make it the

ideal wood for violins and other string instrument. It is the reason why Paneveggio

is called the Forest of the Music Trees.

|

| Slow and Painstaking Work |

The red spruce trees that

grow there have been scientifically proven to have special characteristics, a

certain elasticity and particular honeycomb like structure that mimics small

pipe organs. It is this unusual structure which allows the efficient

transmission of sound waves and amplifies sound, making it the ideal wood for

violins and other string instruments.

But not all trees in the forest are music trees.

The best trees are straight

and round with few leaves. When a woodcutter finds such a tree, he first strips

away part of the bark and examines the tree trunk. If he sees small

longitudinal grooves in the wood it is most likely a good candidate. Then he’ll

hit the tree with a heavy hammer and listen to its vibrations. If the

vibrations are strong, the tree is cut down and transported to one of the

several saw mills on the lower slopes of the mountain. There the trunk is cut

into rounds and the growth rings are examined.

|

| Maestro Conia's Workshop |

“If the growth rings are

grainy and evenly spaced,” says Master Conia, “it’s good sign. It means the

tree has experienced intense cold while growing. That greatly improves the

transmission of sound and influences the timbre of the musical instrument.”

But there is more to making

a musical masterpiece than just choosing the right wood. Making a violin was,

and still is, slow and painstaking work and the superstitious violin masters of

old didn’t tempt fate.

|

| An Original Stradivarius on Display at the Royal Palace in Madrid, Spain |

Stradivarius, for example,

would only use wood male red Spruce trees from the Panneveggio Forest. He also

insisted that the trees only be cut during the winter under a waning moon when

their sap was not running. And before he applied the final coat of varnish to

the instrument he was making, he would take it home and put it on the table

next to his bed for a couple of weeks. By keeping the violin close to him, he

believed a spiritual transaction took place between him and the instrument, and

that the violin would inherit a soul.

There may have been more to

Stradivarius’ quirkiness than meets the eye. Even today, when many believe

violin craftsmanship is at its highest peak, the truth is the instruments being

produced can’t match the old in expressiveness and projection. Just what made

those old Cremonese violins so special still remains a mystery.

|

| 70 Separate Pieces of Wood in Each Violin |

The craftsmen working in

Cremona today may not be quite as superstitious as the old Masters but they do

follow the same methods and patterns. You can see how it’s done by visiting

an artisan’s workshop. Just stop in at the Cremona Tourist Information Office

and ask for their list of Botteghe Liutarie.

In the Palazzo

del Comune you'll

find a collection of classical Cremonese School violins, including a 1566

violin made by Andrea Amati for King Charles IX of France and the 1658 Hammerle

violin created by Nicolò Amati. In the Museo Stradivariano on

Via Palestro 17, there are more than 700 objects from the Master’s workshop.

There is a replica of a

violin artisan’s workshop during the time of Antonio Stradivari. It is located

in the Tower il Torrazzo in

the Piazza del Comune. Museum hours Tues-Sat 10-12:30 - and 3-6, Sundays

9:30-12-30.

Cremona

Tourist Information Office (APT)

Piazza del Comune

26100 Cremona

Tel: +39 0382 22156/27238

Paneveggio Forest Information

San Martino di Castrozza

Via Passa Rolle 165

38058 TN

Tel: +39 0439 768867

Fax: +39 0439 768814

Email: info@sanmartino.com

Maestro

Stefano Conia

Corso

Garibaldi 95 (in the historic center)

Cremona,

LO

http://www.stefanoconia.com/

His

violins can also be found at Sothebys, Philips, Bongards and Christies.

Wonderful, exact information (what was looked for and immediate). Will be useful when Italy

ReplyDelete(and Cremona) visited. Thanks!